So, San Antonio. That was a hell of a week. By now, you may have heard that Dr. Kelly Shanahan (a fellow metster and a seriously smart woman) and I had an interesting conversation with a scientific advisor for Komen, Powel Brown. I wrote a Facebook post about it on my personal wall, and made it public. Here’s what I wrote:

This week, Kelly Shanahan and I had a conversation with Powell Brown, a member of the scientific advisory board for Komen. We explained to him that the metastatic community is largely dissatisfied with the small percentage of funding that Komen spends on research, since research is the only thing that will save our lives. I told him that they need to change their split between the national and the locals so that more money is available for research. His response was that he doesn’t believe Komen will change that ratio, and that Komen would not begin funding more research until the metastatic community gets behind Komen. He said that if we want Komen to spend more on research, we should participate in their fundraising efforts. He said that more fundraising would mean more money available for research. I told him there was no way that our community could get behind an organization that chooses to spend its money on things other than saving our lives, especially given that there are other organizations that spend a much larger proportion of their funding on research, including BCRF, which now outstrips Komen in dollars spent annually on research. His response was that if that’s how we feel, we should just support BCRF instead. And he walked away.

This is what a national leader for Komen feels about the metastatic patient. We are disposable because we don’t fundraise for them. Do not let them fool you into believing they care about us. Our lives don’t matter to them. And that’s why Komen is irrelevant to us. We must and will save our own lives.

Upon reading this, I think I broke the metster portion of the Internet, since the post was shared over 1000 times and the awesome Eileen aka Woman in the Hat also wrote about it on her blog, for which I am super grateful. I got a lot of people saying how brave I was to share this conversation, to expose what a national advisor to Komen actually thinks about us and our disease. But you know what? When you’re dying, when your friends are dying, I mean, what do I have to lose? What’s Komen gonna do to me that cancer already isn’t? Brave is when you’re scared and you do it anyway–but I’m not afraid of Komen, so it’s not actually bravery. It’s just giving no fucks, combined with a whole lotta anger.

One of my friends emailed Komen CEO Judy Salerno about this. And this was her response.

I appreciate the opportunity to address some of the issues you raised in your email to us this weekend. I’m not sure there’s an answer that will satisfy everyone, but this is important to me and I hope we can have additional conversations.

This starts with an explanation from me about why we do what we do. I promise to be very candid, as you’ve been with us.

As I write this, I’m thinking about the people I knew who have died of metastatic disease just this past year. One was our Komen Ozark executive director, another was a longtime Komen patient advocate, and another was a dear friend of mine who died last month. There are others, of course, but I mention this so that you know that this is personal to me, as it is to everyone at Komen.

I’ll start with our approach to research. Jill, as you know, we’d like to fund everything that needs to be funded, but the reality is that this disease is complex, its impact is huge, and our resources are finite. Finding cures requires a comprehensive understanding of how breast cancer starts, how and why it spreads, why it affects some women differently than others, and how to better treat it or prevent it.

This is why we at Komen fund along the entire research spectrum, because there are many issues to understand and solve, and what we learn in one area may lead to answers in another area. Some of our research projects – in biology and causation, for example – are not specifically labeled as metastatic research but could have applicability to metastatic disease. That said, we’ve devoted half of our new research funding specifically to metastatic disease in 2015 because it is a priority for us.

Finding cures through research is, and always has been, at the core of our mission. But we also know that too many people die of breast cancer because they can’t access high-quality healthcare. For that reason, a significant portion of our mission spend is directed to programs in thousands of communities that pay for things like insurance co-pays, diagnostic tests, patient navigators, and other medical expenses, as well as what we call treatment support: transportation, childcare, emergency living expenses, and other things that often stand between patients and their medical care. A list of what we and our Affiliates fund in the community is available here.

Some mistakenly label the community health aspects of our work as “awareness.” It is, in reality, the in-the-trenches work that must be done to help women and men who face breast cancer today, at all stages of the disease. Komen is the only breast cancer organization that funds this kind of large-scale community health work along with a large research program. We do this because it also contributes to saving lives.

Finally, Powel Brown is an esteemed scientist and a member of our Scientific Advisory Board, which serves as an advisory body to Komen on research and cancer science, but does not advise on our organizational or operational priorities. He was not speaking for the Komen organization, but he is correct that our ability to fund research – or any of our work – depends on the amount of money we’re able to raise every year through our donations and fundraising events. This year, we’ve begun a new donation program which gives donors the ability to fund metastatic research directly. We encourage those who are interested in supporting metastatic research to help us fund those projects through this directed donation program.

We also want to keep the conversation going, through the many venues we have to engage – the Metastatic Breast Cancer Alliance that we helped to found, with metastatic patients directly, and by exploring joint funding of metastatic research with other cancer organizations.

Like cancer itself, these issues are complex and not easily resolved. There are areas where we may not always agree, but I want you to know I am listening. More importantly, I have identified metastatic disease as a Komen priority, meaning continued investment in metastatic research and help for metastatic patients. Our common enemy is this terrible disease.

Sincerely,

Judith A. Salerno, M.D., M.S.

President and CEO

Susan G. Komen

OK, so, there’s a lot to unpack there. Let me start at the beginning.

Saying “I have friends who died of breast cancer so this is personal to me” is the equivalent of a white person saying “I have a black friend so I’m not racist.” Excuse me while I roll my eyes and thank you for deigning to be friends with the likes of us. If it’s so personal, why is Komen spending so little on research, which is the only thing that will save our lives? Actions show what’s really in your heart, not words. Not platitudes about how much you care and how you’re listening can substitute for concrete actions to support our community.

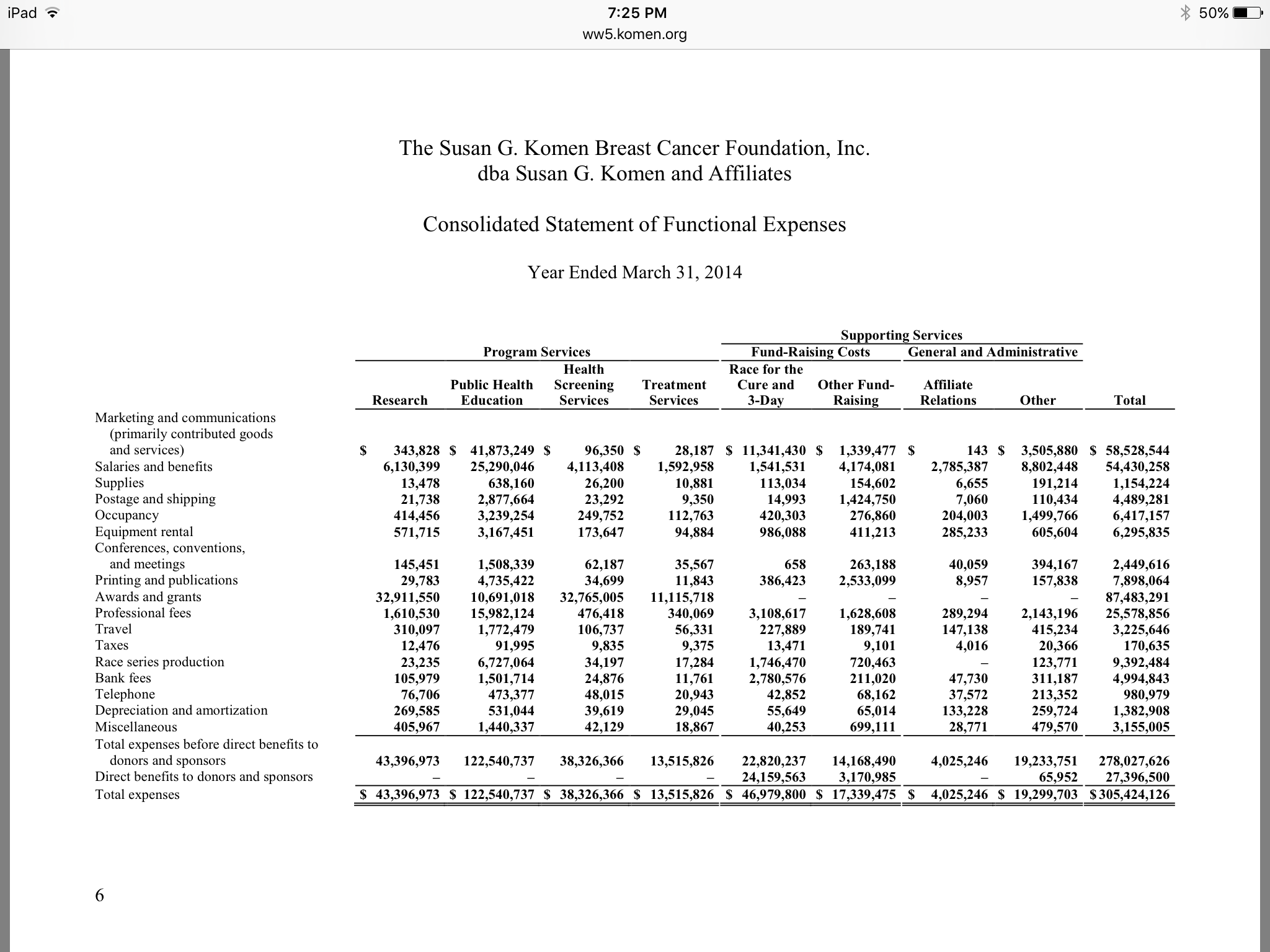

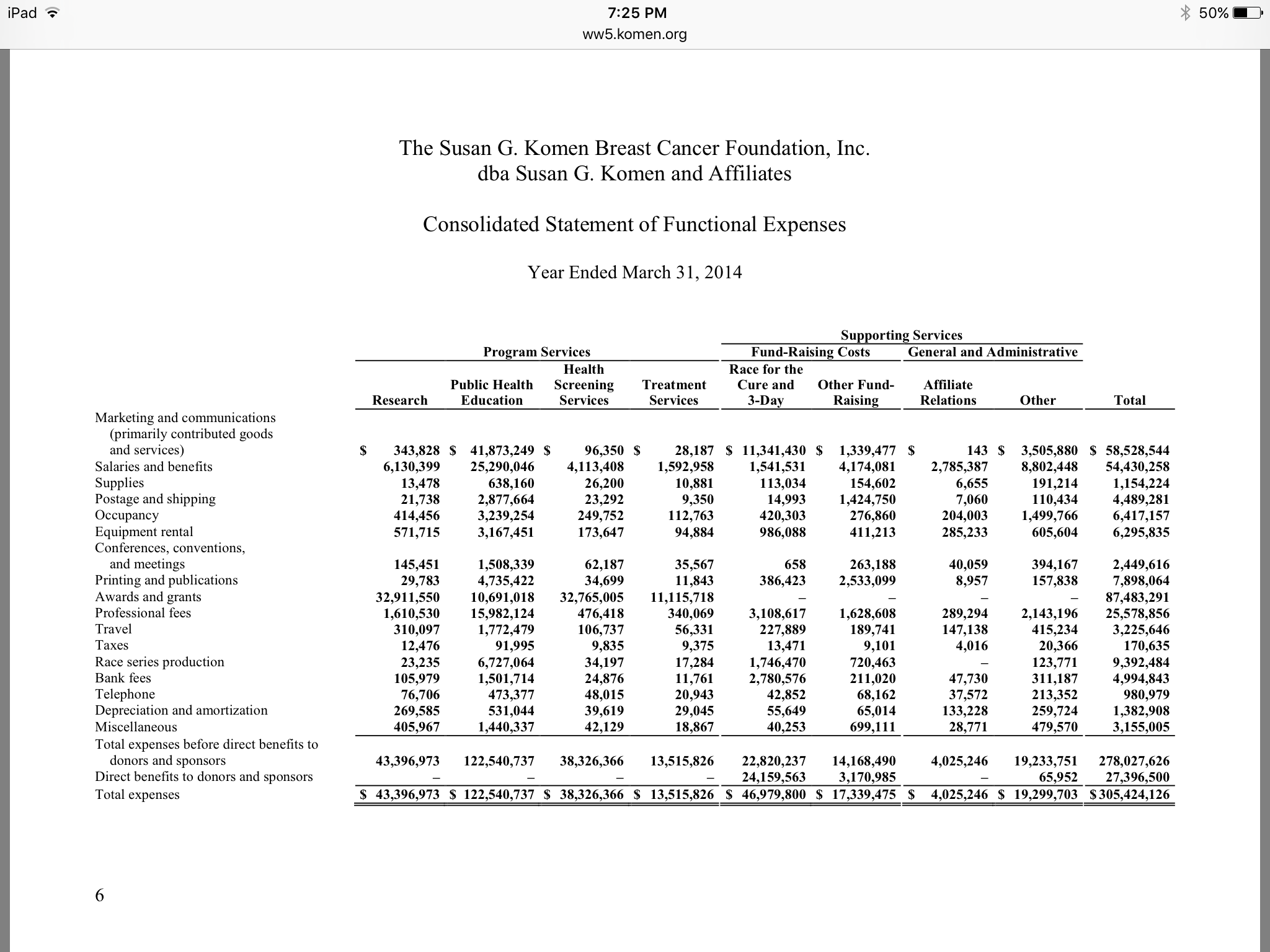

Then there’s the accusation that we’re criticizing Komen for spending money on direct patient support because we conflate it with awareness. NO. The metastatic community is not stupid. We know that direct patient support is important, and we know that it is not awareness. Please don’t insult our intelligence. What we’re criticizing is the amount Komen spends on what it calls “education.” Here’s a screenshot of the most recent audited financial report from Komen–from their website, so this is THEIR data.

See where it says “Public Health Education”? See the total in that column? Yeah, it says $122,540,737. See what it says for “Research”? $43,396,973. Those numbers are the opposite of what I believe they should be. But the problem is, see where it says “Marketing and communication” in the column on the left? See what that total is for “Public Health Education?” $41,873,249. Of their public health education budget, nearly $42 million of it was literally spent on advertising. Nearly as much as their entire research budget. See, with “education,” you can count your marketing expenses as a program expense by putting something educational on your marketing materials, and then it looks like you’re spending a bigger proportion of your budget on the mission and less on administrative expenses. Can’t really do that with research.

So no, I’m not complaining about the $13 million they spent on “treatment services.” I’m complaining about them spending almost 10 times that much on awareness, a third of which is actually marketing.

Then there’s the part about how Dr. Brown doesn’t speak for them. OK. Then maybe don’t put him in front of the Komen booth at the largest breast cancer symposium in the world and let him talk to people? Maybe don’t put him on your scientific advisory committee?

My favorite part, though, is that after saying Dr. Brown doesn’t speak for them, she confirms the core of the offensiveness of his comments: Komen won’t do more research until they get more money. An organization that spent $122 million on awareness can’t be bothered to shift any of that money to the only thing that will save our lives: research.

And then there’s the standard “We’re listening” stuff. No you’re not. You’re talking. And you don’t even realize that you’re lecturing metastatic patients. We’re dying and you’re telling us we shouldn’t complain that you’re letting us die. See what I mean about “I have friends who died of breast cancer so this is personal for me” being eye-roll-inducing?

And this is why Komen continues its steady decline into irrelevance. It’s living in the past, and this is why we as metastatic patients have to realize that they’re not coming to save us. We’re going to have to save ourselves.

Like this:

Like Loading...